The first post is here.

I want to run local models on my PC, and I want to do it while learning as much as possible in the process. What do I need to do so?

1. The model

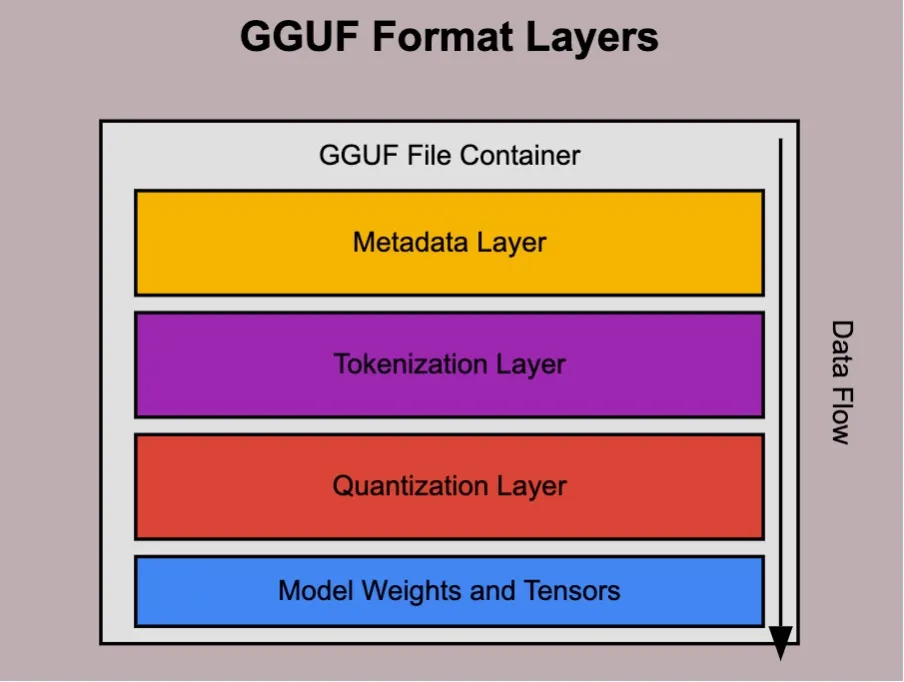

To run a model, we need the model itself. This model will be a file, or a set of files, detailing the structure of the model (layers, sizes, types) as well as its values. Also, some metadata with information about the model.

There are different formats to pack a model and distribute it: GGUF is the most common, but there are several different options, some of which this Hugging Face article describes.

1.1. Quantization

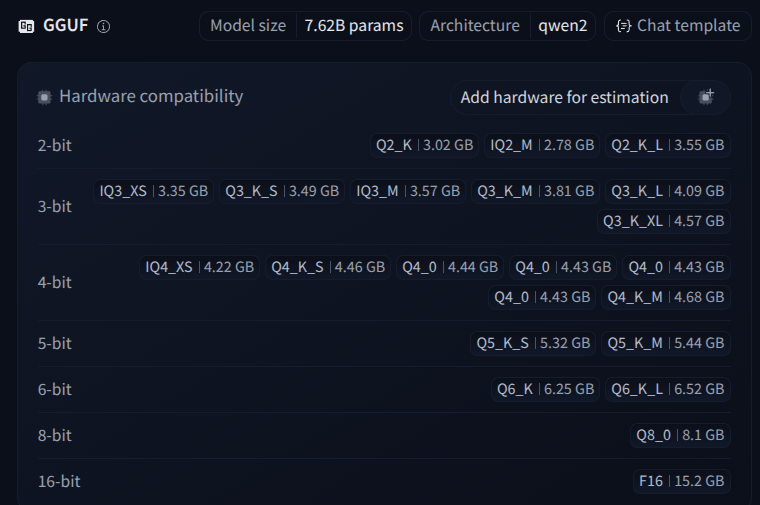

The size of a model is determined by its number of trainable parameters. A typical open-weights model suitable to run on a personal PC has a few billion parameters. For example, Qwen/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct has 7 billion (that’s the 7B part, although technically it has 7.61B). This model uses 16-bit floating point numbers, so 2 bytes per parameter means the model size is 15.2GB. All this data has to be loaded in memory, ideally into the GPU VRAM. (As a reference, state-of-the-art commercial LLMs like GPT-5 likely have trillions of parameters.)

To make it easier to fit these models in consumer-level GPUs, these parameters can be quantized: we reduce the precision of the parameters to make the model smaller at the expense of some accuracy.

The GGUF format usually includes several different quantized versions inside the same model file. For example, this GGUF version of Qwen/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct contains quantizations ranging from 8 bits (8.1 GB) to 2 bits (3.02 GB).

1.2. Tensors

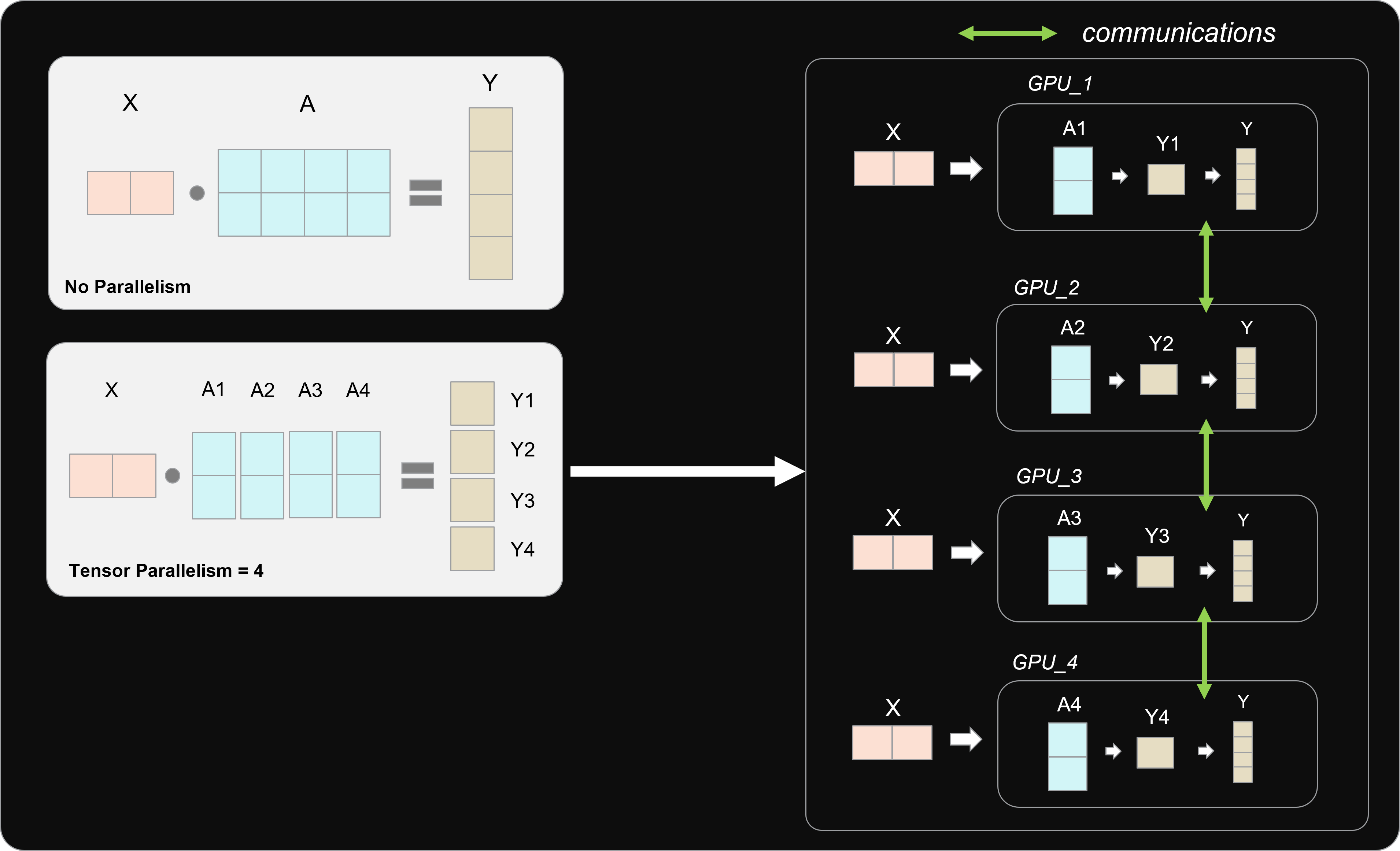

Parameters in a neural network are represented as tensors. We can think of tensors as the general term for scalars, vectors, matrices, and groups of numbers of more than 2 dimensions. So running inference with a model is just adding and multiplying tensors. Adding and multiplying tensors is conceptually very simple, but computationally very expensive. GPUs are way more capable of doing this than CPUs because they can parallelize the floating-point operations needed. Optimizing these operations is the key aspect of this setup. Generating a few tokens per second requires billions of operations per second, and any minimal improvement may be significant.

The GPU itself doesn’t know about tensors, though. It just knows how to operate with floating-point numbers with a lot of parallelism. So GPU manufacturers create software with different levels of abstraction to make it easier to run these pieces of hardware. For example, NVIDIA has CUDA, which lets you easily do math in parallel; cuBLAS, which uses CUDA to expose an algebra-oriented API; and also TensorRT, an SDK specialized in deep learning inference, which in turn uses cuBLAS.

2. The inference library

At the most basic level, an LLM model is an algorithm that takes some text and returns some other text. The model includes a layer, usually the first one, to convert the text into numbers. These numbers are then processed by the rest of the layers, and the result is converted to text. This whole process is called inference. All the billions of parameters we saw before are applied in different ways to the input data to generate the result. The inference library contains the code to execute all these operations.

Different options might have different levels of abstraction. For example, we mentioned TensorRT for general deep learning inference. But NVIDIA also provides TensorRT-LLM, designed for LLMs. Both options are available for NVIDIA GPUs only. Also, they are not just engines to generate tokens; they provide a lot more, as we’ll see in the future.

Another popular option is vLLM, a library-server with support for different hardware options.

And, of course, the most basic and known library, llama.cpp, which we’ll use to start the tests in the next post.

3. The user interface

I haven’t mentioned some of the most common tools associated with the “running LLMs on my PC” idea. The reason is that these options are just wrappers for accessing inference libraries conveniently. I’m focused now on understanding what is going on when running a local model, and trying to figure out what is the most performant option for me, so these tools are a distraction for that.

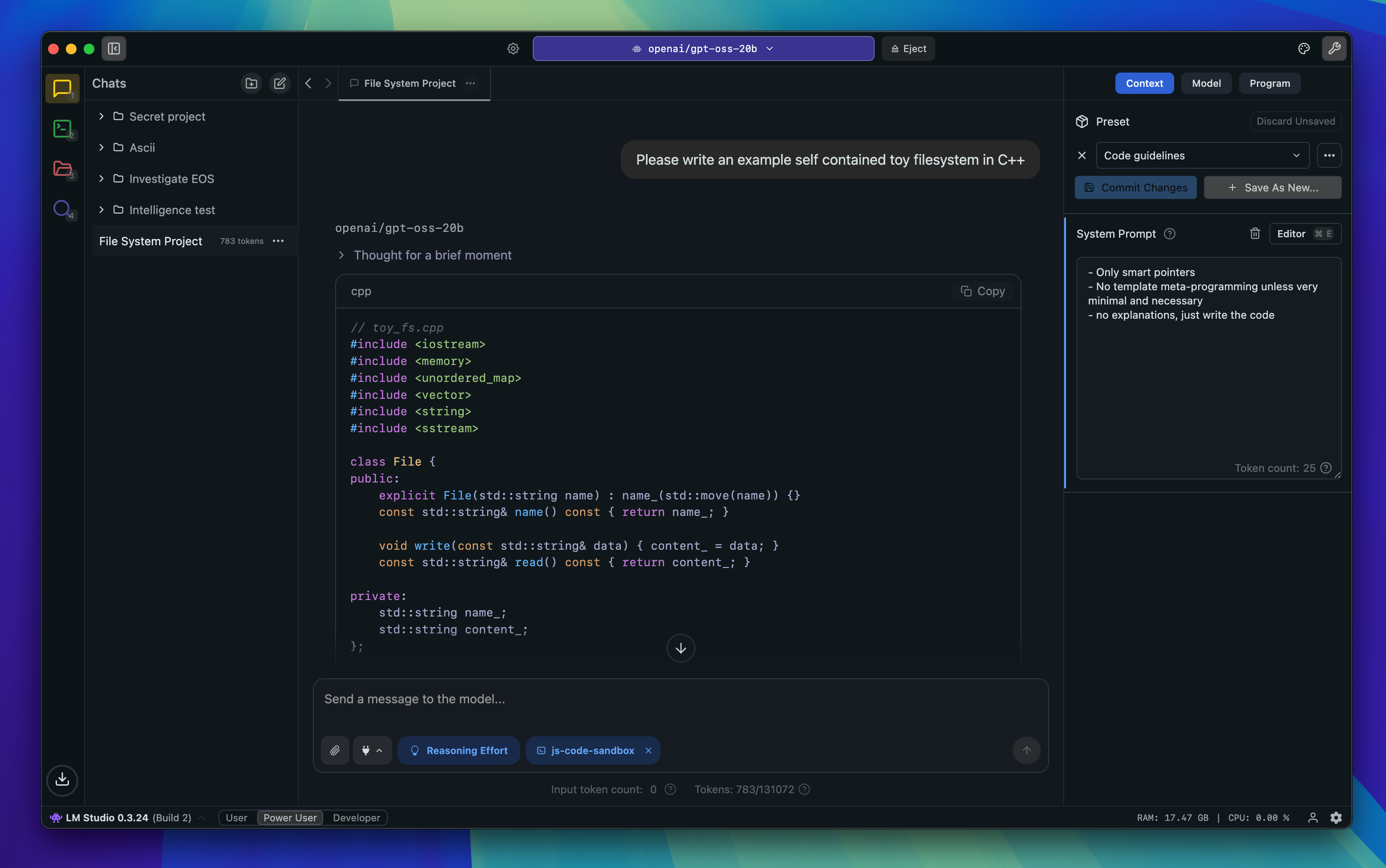

But for the sake of completeness, a few mentions: LM Studio is a non-Open Source tool with a full-fledged UI to maximize convenience. Open WebUI is an open-source alternative to LM Studio, and so it is Text Generation Web UI. One of the most popular options is Ollama, a command-line tool that simplifies the entire process of downloading, running, and interacting with the model.

Feel free to download and test any of these tools, but if you feel adventurous and want to compile your own LLM library, join me in the next chapter.